A psychoanalytic investigation into the sexualised representation of women and fish in Salvador Dalí’s ‘Dream of Venus’ and Katsushika Hokusai’s ‘The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife’ — by Peach Doble

‘I’m still a man, he thought with his last remaining spark of masculinity... I’m still a man, in spite of the blasted shellfish... And he stuck out his chest and almost fell flat on his peaked oyster-coloured face.’

(Fisher, 2018, p. 80)

(*TW – references to sexual assault)

We have long been hooked on that enduring erotic symbol, the humble fish. It has been sexualised, objectified and consumed by humans in abundance ever since the feasts of Ancient Greece. And yes, there are obvious aesthetic similarities between seafood and human genitalia. These similarities arouse and excite the brain when seafood is being eaten, looked at, or smelt. The aromas, textures and appearance of seafood have ‘great influence on the genesiac sense, and awakens the instinct of reproduction in the two sexes’ (Brillat-Savarin, 1825, p 42). Because they are anatomically comparative, sea creatures and genitalia become symbolically interchangeable.

But it’s not just on the menu in Ancient Greece; in traditional Chinese medicine aphrodisiac potions are made with seahorse and considered cures for impotence. The Aztecs gave offerings of seafood to their rain god to encourage fertility. In Japan, puffer fish, sea urchins and eels have been considered intoxicating aphrodisiacs for thousands of years. Whether it’s an idea passed down from our ancestors, or intrinsic to nature, moist oysters, slippery tentacles and meaty lobsters are a Freudian feeding frenzy for symbolism and analysis.

It is fitting that the word ‘aphrodisiac’ comes from ‘Aphrodite’: the Greek Goddess of love, fertility, pleasure and beauty. Aphrodite and her Roman counterpart Venus were both said to have been born from the sea in a shell made by the foam surrounding the castrated genitals of her father. It is Venus that has been the focal point for most Western erotic art for thousands of years. Botticelli’s ‘Birth of Venus’ is perhaps the image that immediately springs to mind. His Venus features – cut, enlarged and collaged – on the front of Salvador Dalí’s 1939 World Fair exhibit ‘The Dream of Venus’.

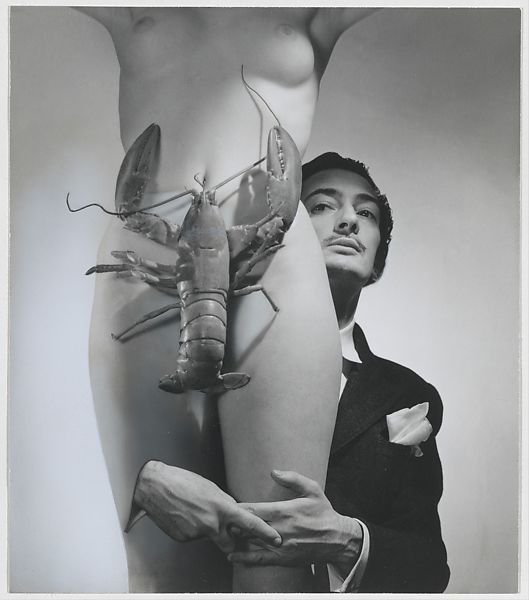

Dalí’s walk-through, undersea fun house was designed to take the audience inside the unconscious mind of the sleeping goddess Venus, filled with surreal thoughts and erotic fantasies. Upon paying your fee into the fish-head ticket booth, you would have entered into a dark hole between the spread legs of Venus. Once inside, you’d find two parts to the exhibit: the ‘wet tank’ and the ‘dry tank’, and a shoal of nearly nude female performers, there to entice and entertain the audience. Although abandoned by Dalí on the day it opened, the installation was a 3-d Surrealist realisation of Freud’s psychoanalytic theories, designed to promote Surrealism in America and provoke the audience.

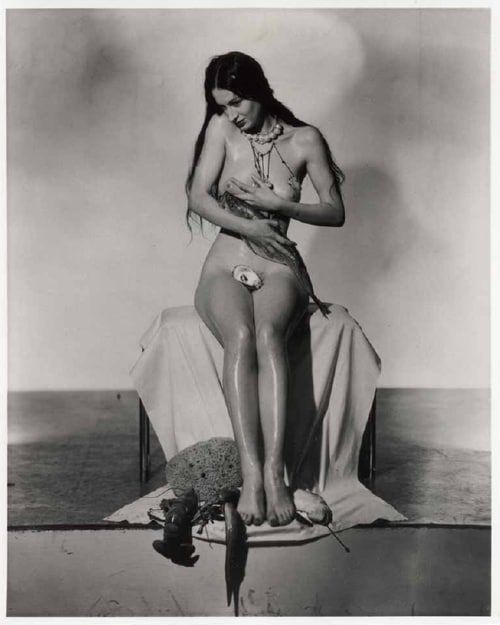

Salvador Dalí often took direct and literal inspiration from Freud, drawing specifically from Freud’s castration theory for his ‘Dream of Venus’ exhibit. In the run up to the exhibition, Dalí hired two photographers to capture enticing promotional images. Nude female models were styled and directed by Dalí, wearing real sea creatures as accessories and shells as jewellery, and were asked to pose erotically for surrealist photographs. The models were acting as Venus, then given props and arranged in sensual positions. Figure 2 shows the model with a real lobster strapped over her genitalia. Its tail is phallic in appearance and placement, and hangs suggestively from between her legs. The lobster in the photograph poses a very real danger. Its sharp claws and spiny shell make it the perfect symbol of castration – it is ready to snip or chop anything in its path. The lobster and the woman thus represent Dalí’s fear of losing his penis, and his fear of the woman – who is out to castrate him.

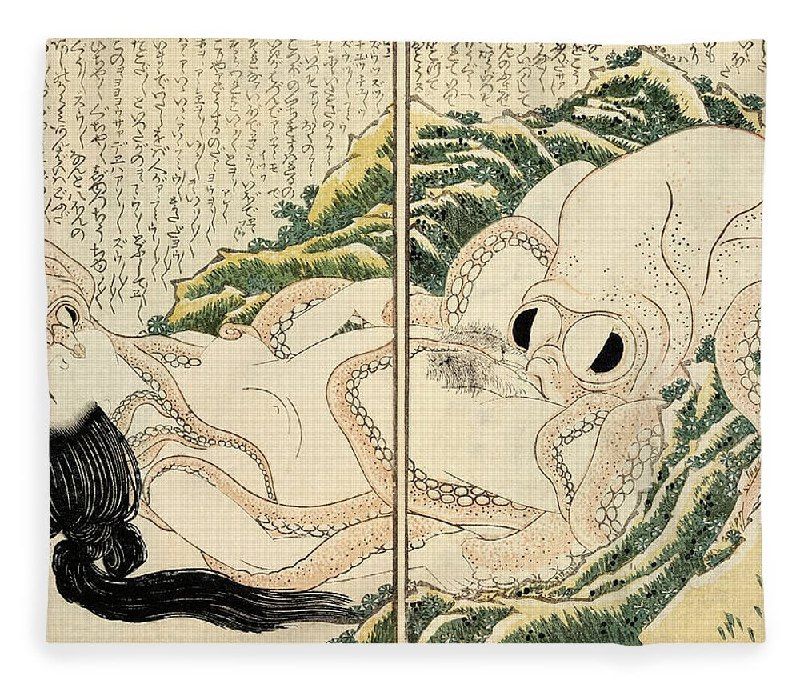

Rewind one hundred and twenty-five years to Japan’s Edo Period, and find Katsushika Hokusai creating ‘The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife’. The piece is a form of erotic Shunga, a popular genre of Japanese woodblock printing that portrayed the sexual fantasies of the time. Also known as Ukiyo-e, which translates to ‘pictures of the floating world’. Like contemporary pornography Shunga often had a narrative. In ‘The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife’ Hokusai quite literally turns a Japanese mythical story on its head: the painting depicts a woman being sexually pleasured by two octopi. The legend that Hokusai based this image on is Taishokan; a tragic story of female self-sacrifice. Tricked by her husband, a young shell-diver must retrieve a precious stolen jewel from the underwater dragon king in order to ensure her son’s future. She dives into the sea kingdom, takes back the jewel from the dragon king, but doesn’t make it to the surface. Instead, she cuts open her chest to hide the jewel, which is then discovered inside her dead body. The story was incredibly popular, but only later eroticised and parodied into works of Shunga. Often misread, ‘The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife’ is awash with complex puns and visual metaphors from Edo period culture that reveal far more than meets the eye (Talerico, 2001).

The narrative and inspiration behind Hokusai’s print derives from Taishokan, a tale that originally held religious and moral intent. However, this tale was distorted and eroticised by Hokusai and subsequent Shunga artists to become a piece of provocative art. In eroticising the story, the woman has been fetishized and sexualised once again, and turned into a fantasy for the artist. Similarly to Dalí’s image, this fetishisation of the female body is to keep the woman ‘reassuring rather than dangerous’ (Mulvey, 1975, p. 14). The idea of the woman as dangerous is a subject frequently explored by male artists; the femme fatale, the siren, or the Medusa complex, are all well illustrated throughout history. In Greek mythology, Medusa was a monstrous but bewitching snake-headed gorgon. She could petrify and turn a person to stone with a glance. As described by Martha Kingsbury, the woman is ‘both seductive and destructive’ (1972 p.185). This fear of the female power, her femme fatale, triggers the male desire to restrain and dominate it, creating the Medusa complex (Mayock, 2013)

In Ovid’s Metamorphoses Medusa began as a beautiful girl who was raped by Poseidon – god of the sea – and then punished for it, disfigured, and given a head of serpents (Bowers, 1990). Like Medusa, the Fisherman’s wife could be seen as a fallen woman. But instead of falling from beauty to horror, she falls from virtuous to sex object. Originally the star of a heroic tale, Hokusai instead makes her ‘seductive’ to keep her from being ‘destructive’. Kingsbury continues to describe the aesthetic attributes of the femme fatale woman in art as having ‘the suggestion of ecstasy in their heavy eyelids and thrown-back head [which] signifies a loss of control in their moment of triumph’ (1972 p.183). Here, the Fisherman’s wife shows just that. Her eyes are closed and her back is arched in an orgasmic position. She has her grasp on the tentacles, signifying her control over the situation. However, she is lying down, as she has succumbed to the predisposed sexualisation of her body by the artist. Therefore, Hokusai portrays her as a threat, only in order to defeat it.

Within the works discussed, these men, because of their psychological entrenchment into patriarchal patterns of desire, are unable to give agency to their female subjects. So, it would seem that the titles of the works should really be read as Dalí’s dream – of Venus, and Hokusai’s dream – of the Fisherman’s Wife. But whilst the male interpretational fantasy of the fish and the woman has been examined, an interesting further avenue to explore would be female interpretations. Bowers posed a counteraction to the male gaze: the female gaze. This is where women regain their identities and take back control of their own sexuality (1990). By moving away from the phallo-centric Freudian approach, and the misogyny of the male Surrealist movement, it could bring to light a fresh perspective, and reveal the female artists previously hidden from the limelight. Whether nature or nurture, it’s only after trawling one tiny corner of the art-world that you realise there’s plenty more fish in the sea.